|

I thought this would be perfect to bring back for Halloween since I'm doing it again myself this year! I first posted this in 2013, but it's still a fun and easy-prep activity almost 10 years later. (This is a Throwback Monday bc I couldn't wait until Thursday!)

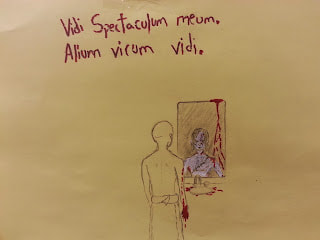

above. It's really amazing how much can be communicated in just a few words. When I read it, a lightbulb went off in my head and the article was filed away in my brain somewhere under "There Has To Be Some Way I Can Use This In My Class" (long file name, longer file contents).

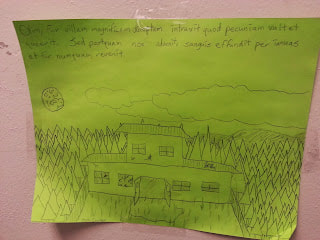

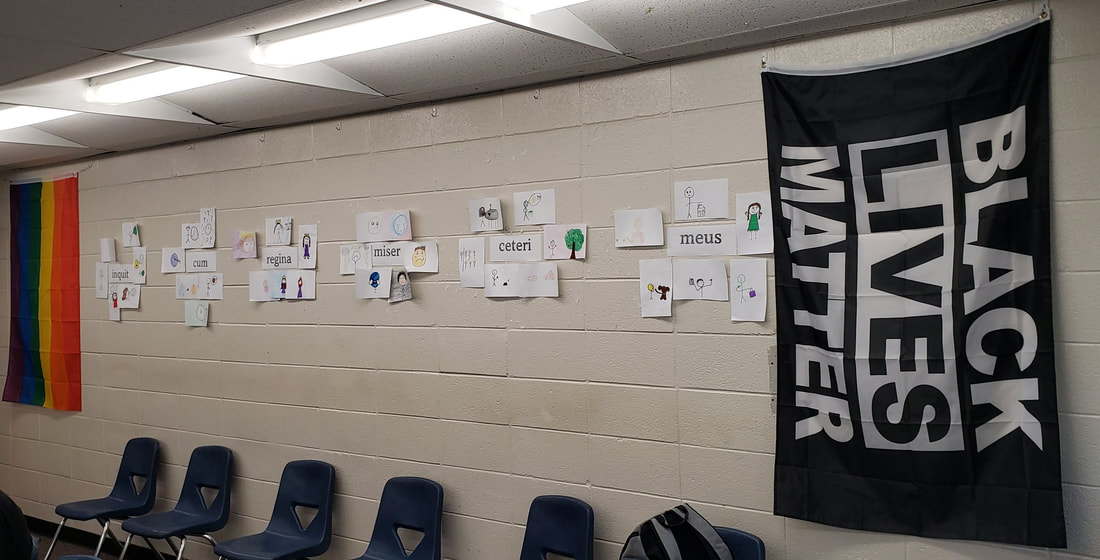

Last week, inspired by the holiday and expecting my classes to be at least somewhat active (says ten years' previous Halloween experience--and who am I to argue with experience?), I decided that I had found the right moment to use this idea. I began the class by handing out and going over a compilation of horror vocabulary, Vocabula Terrifica, that Miriam put together earlier this month. After running quickly through the vocabulary, I told them about the io9 article and read a couple of the examples in English. Then I put them into small groups, where they were asked to write Latin two sentence horror stories and illustrate them on a colored sheet of paper. Lastly, they were asked to tape them on the wall when they finished. The few groups who finished early were able to go around and read other groups' stories. It was a nice way to spend Halloween.

0 Comments

Technically this was not a previous post, but a transcription of a speech I gave as the keynote speaker on day 3 as a co-host of the Stepping Into CI summer workshop in 2020, but I think it still counts as a Throwback Thursday post. When I first coined the term “Caring,” for CI it was a pithy way to encompass everything left over after you explain “Comprehensible” and “Compelling.” How do you describe keeping student anxiety low, making students feel valued and heard? How do you describe building relationships and trust?

Caring. After I added the third “C,” it took on a life of its own in our department [see this post by Keith Toda] and forced us, as a group, to look at ourselves and our practices and always question: “did that lesson show Caring?” Caring has become my favorite “C.” Caring is why I became a teacher. “I want to be the teacher that shows each student that someone cares.” I think that was literally part of the teaching philosophy I had to write in my one and only education course. The way I show I care has morphed over the years. It has grown. It started with seeking out students in special education and making sure they have what they need in my class. With learning that a typical class structure, which I thrive in, can be actively harmful to some students. With taking my students as they are, as they choose to be, and calling them by the names that they asked me to call them. With listening. With respect. With care. Over the years, caring has become more. It has become educating myself. Learning how the brain learns and incorporating that into my classes. Researching about the effects of socio-economic factors, racism, sexism, ableism, and homophobia in my classroom so I can learn to watch for it and do my best to fight it. Learning to battle uncomfortable topics head-on because I can’t dodge the reality of slavery in Rome by calling slaves “servants,” and doing so does my students, all of my students, a disservice. Caring has made me look at my lesson plans and see the gaps. I had worked to make personal connections with my students and make them feel seen by me (because I see them) and loved by me (because I love them), but I had never thought to examine the materials I offered them to see if they could see themselves there. They couldn’t. That’s a gap. It’s a gap I’m still mending. Caring is evaluating everything I do to make sure that it’s in the best interests of my students, not just what I’ve always done, not just what I’m comfortable with, not just part of the canon. Caring is making myself uncomfortable so I can make my students comfortable. Because when students are comfortable, when students feel seen and heard, when they see themselves in what we do, that is when they learn best. They learn they are worthwhile. They learn they are worthy. And then you can teach. This first ran in Pomegranate Beginnings in January, 2017. I thought with school starting or about to start for some of us, we could all use some easy ideas!  An image from a micrologue I made for my students. An image from a micrologue I made for my students. "Dictatio" is one of the few words my students dread in my class. I'm going to admit that it's a nice break for me--requiring only voice and repetition and pretty much no creativity--and it sometimes finds its way into my plans simply because I need a day that does not require all of my energy. Dictationes fall within my Comprehensible Input toolbox because as long as I keep the vocabulary limited, the dictated sentences provide valuable repetition. But students rarely enjoy it. Writing down a dictation is not a compelling activity. I have tried to spice it up by making the dictatio its own story, or even a lead in to the main story I'm working toward but missing crucial information. That has its place, and it helps. But it does not keep students from moaning "eheu!" the next time they see "Dictatio" listed on the day's schedule. This year I have only done a traditional dictatio twice so far, and I am working to slowly replace the practice completely for myself with equally low-stress but much more compelling versions of sentence listening and writing. There is something useful for acquisition in writing something down, and auditory repetition of understandable messages is universally good for acquisition. So I don't want to give up those strengths. I just want less "eheu" and more "euge" while students acquire Latin. Keith Toda often cites Carol Gaab's statement, "The mind craves novelty." If I simply replace dictatio with just one activity and do it every other week or so, students will grow as bored of that activity as they are of dictatio. Instead, I've been gathering dictatio options. With the new semester coming up, I thought I'd share the dictatio options I keep on hand. I hope to continue to add new twists and ideas to this list.

One way Miriam and I were able to bring purpose to our dictation type activities last quarter was to either

This first ran in Pomegranate Beginnings in May 2013. I still agree with it and, almost a decade later, find standardized testing in the same place, if not worse. I have moved on to teachers' unions instead of a separate organizing force (which has ceased to be anyway), and still push for change. A couple of weeks ago, I was monitoring a test.

It was my third test of the day. I was bored. This particular test is a state-mandated standardized test that asks teachers to "actively monitor"--meaning no grading, no planning, no computer, only watching students stare at computer screens--students to make sure the test is as secure as possible. My job was to walk around, not read the test at all, make sure no one is looking at anyone else, etc. By the middle of the first test I felt like going crazy. I had random urges to jump around and wave my arms spasmodically in the air, just to change my pattern: weave this way between the computer tables; now this way. I will admit to a certain level of hyperactivity and a pretty persistent need to keep my mind busy that often requires a pen and paper (at least) to record my thoughts. This walking in circles thing while watching kids stare at computers, listening to mice click, scroll, click, is about as opposite my natural modus operandi as it gets. When I first started teaching I used to carry a stone in one hand when I gave tests in my classroom so I could at least fiddle with something, but I didn't bring one to this test. It was during one of my passes between computer tables that I noticed it. Thin, shaky lines, obviously originally written to be hidden, but now betrayed by a simple rearrangement of cardboard dividers, spelled out one student's despair in three straight-forward words: school sucks balls. School sucks balls. I silently agreed with the concisely authored phrase as I did a quick turnaround just in case students might think they knew my path well enough to steal a glance at someone else's test--a test that contained different questions in a different order than their tests. In that setting, at that moment, how could I disagree? There was no learning, no spirit of inquiry, no empathy, nothing that makes school special, in that setting and at that moment. There was the test. And, before that, there was preparing for the test. Teaching this year has been an eye-opening experience. Before this year, I was already against standardized testing, pre-testing, interim testing, post testing, and field testing (we did all of these this year--none of that is made up). I follow SOS: Save Our Schools [the link has been removed as the site is defunct now in 2022], a movement against testing as a means of measuring student and teacher achievement. I recognized the invalidity of a standardized test as a means of measuring either intelligence or learning even as a preteen who was extremely good at testing. I have hated standardized testing for a very long time. Yet, I had never experienced teaching a class that culminated in a standardized test. This year was the first year I've taught Language Arts in a public school. Previous to that, I have mostly taught Latin, an untested field, and have had the freedom to tailor my classes to my students' needs. If they knew the current concept and were ready to go on, we did. If they needed more reinforcement of a concept, we spent more time on it. I created a community in my classrooms; generally my Latin classes have been joyful and celebratory, filled with fun, jokes, and a personal relationship with my students that let me experiment with methodology and let them tell me with honesty what was working for them. I still had two Latin classes this year, but I also taught three Language Arts classes. The difference has been astounding. I feel like I only got to know maybe a fifth of the students very well. We were rarely creative. We were rarely laughing. We were rarely having fun. I spent most of my time in the front of the room, lecturing, or pacing through the room while kids read, worked on worksheets, filled out forms. I should say, this is not my school's fault. My administration is amazing and supportive--I have never seen such a cohesive and reasonable group of principals. My course team for Language Arts has bent over backwards to help me teach as effectively as possible and has been there for me every time I had a question--and that's been often. Instead, it's the fault of the current push to punish schools and teachers for past trespasses that rarely have to do with anyone who is now in the field. The current cry of "accountability" has spawned a testing craze that makes a huge amount of money for textbook companies and hurts everyone else in education, especially the students. My students never got to experience the joy of enjoying a great book, never got to celebrate characters and revelations, connections between themselves and literature. Instead, I got to spoon-feed them as much information as I could so they could be ready for The Test. The Test, a state-mandated standardized test, was worth 20% of their grade. Everything I did in class ultimately revolved around The Test. And my kids, already convinced they don't like spending eight hours a day locked in a building being told what to do, found class boring, tedious, uncomfortable, and uninspiring. So did I. Every day I had both subjects, Language Arts and Latin, juxtaposed against each other as a clear illustration of the difference between a standardized and unstandardized subject. Every day I would so enjoy my Latin classes that I came to dread facing my Language Arts classes and their lack of motivation. It wasn't the students or the subject, it was the way I had to approach both. All my spoon-feeding and worksheet-pushing achieved its goal; nearly all of my students not only received a passing score on The Test, but received a good score, one that improved their grade average in my class. However, I know, from their expressions every time we started a new reading, that they got no joy in my class, found no new literature to love, and generally think Language Arts is one more class that they need to "get through" to graduate. This is no way to educate life-long learners. As things currently stand, "school sucks balls." I only hope that, as this current unfortunate generation of students graduates and gains control of our politics, things will change and this trend will be remembered in history as the mistake and disaster that it is. This first ran in Pomegranate Beginnings. I thought it might be fun to review a simple idea that could be easily incorporated into almost any culture-based lesson plan, and discussed in either the Target Language or students' language of origin.  I love Legos. As I type that, I realize that I start my posts with those words a lot: "I love". I think, though, that it's my passion for all the things I do in class that lets me know I'm in the right place. I always have something to get excited about. Today, it's Legos. Legos are amazing. You can use them to make almost anything. I remember the first time I got a Lego piece that had a hinge. It opened my building world in a new way--Legos with moving parts meant building airplanes with functioning cargo bays, rockets with a door for the astronauts, a drawbridge, and, with a bit of thrust on my side, a sort of catapult that worked. I remember these different projects because through Legos, you get to imagine, plan, and construct a concept. It becomes personal. I can't bring my students to Rome. It'd be neat, but it's also prohibitively expensive, so only a few would be able to go, even if I were in a position to design and carry out a student trip. I also can't bring Rome to my students. Not only is this also prohibitively expensive, I am pretty sure there are laws and regulations regarding moving large marble (okay, marble-faced) ruins between nations. I can, however, have my students build Rome. I would not even be the first person to do this. Over the years it has become tradition to ask students to build a model of some part of Rome: the Colosseum, the Pantheon, the temples and aqueducts and streets (it's especially fun to build Roman streets using food!). Building was a major part of Roman life and experience; Rome was always under construction in some form of another, much like cities today. Romans were known for and proud of their engineers and architects. Recently, though, thanks to a student's idea, I asked students to bring in Legos. Any they would like to donate. We didn't get a huge collection going (though now I know I want a huge collection, so it will happen in time), but we got enough to designate some Legos to each of five groups of students. We had hit a section of the book that discussed Roman military camps, and students were not really diving into that particular cultural topic. We needed a way to connect to the camps emotionally, or at least personally. Legos make connections. Almost all children play with Legos, which means there is automatically a positive emotional response to the nostalgic toys. In the five groups mentioned above, I asked students to do their best to rebuild the Roman military camps they saw drawn in their textbooks. They had a pile, or bag, or box, of Legos and their ability to convert concepts symbolically. Each group worked together diligently, instructing, sometimes arguing with, each other to create the best representation of a Roman military camp that they could build with a limited supply of Legos. It was fun, and each group came out of the activity with the ability to describe the camp layout to me. Next year, I want to do something similar, but take it much deeper.

When we learn about the layout of a Roman city, why not build a Roman city? It can be done cross-class, with groups in each class responsible for different parts of the city. I can create a map layout on a cheap, dollar-store shower curtain, and they can piece their city together on the map. We can follow up with "tours" of the city (maybe I'll bring some of my son's minifigs--the Lego people--to help focus the discussion), telling stories that take place around the city, and generally using the huge Lego model for a while in order to really help students get familiar with the baths, amphitheaters, etc., in a meaningful way. If I require students to communicate in Latin while they build, imagine the deeper, more creative thought they have to reach in order to get the job done. Yet they will be using Legos, which will make it a much more appetizing type of activity. Building with a familiar and generally well-loved toy will soften the effort it will take to think and speak in Latin. I think the next step would be to move outside the range of Legos and have students achieve simple feats of engineering that reflect Roman achievements, such as aqueducts, catapults, and the arch, with basic supplies such as bendy straws, rubber bands, and popsicle sticks. If they have to solve problems (here are these items, now make this) in Latin, it forces students to use Latin in a very meaningful way. Bringing culture to life using Legos will help my students transition from building-block language to truly mastering it as a communicative force. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

AuthorRachel Ash is a teacher, author, seamstress, mother, wife, and overdescriber. She also loves a good list. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed